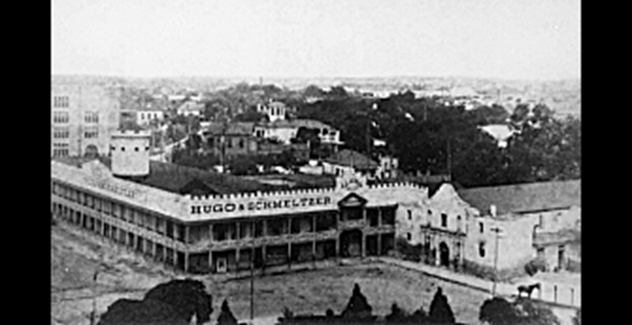

" We now have a truthful book about the Alamo. somehow it seems to have escaped critical attention, particularly, to no great surprise, here in Texas. The book isExodus from the Alamo: The Anatomy of the Last Stand Myth, by Phillip Thomas Tucker. Published in 2010 by second-tier publishers Casemate, this book has not received any reviews by any major national source, nor any attention by any of the Texas newspapers.* Hell I’d have thought that San Antonio,

The Anatomy of the Last Stand Myth, by Phillip Thomas Tucker. Published in 2010 by second-tier publishers Casemate, this book has not received any reviews by any major national source, nor any attention by any of the Texas newspapers.* Hell I’d have thought that San Antonio, which although by population numbers is the US’ 9th largest city has always really been Mexico’s northernmost city, and is also where the Alamo, or what little is left of it, resides, would have paid some attention, but nothing from those quarters

which although by population numbers is the US’ 9th largest city has always really been Mexico’s northernmost city, and is also where the Alamo, or what little is left of it, resides, would have paid some attention, but nothing from those quarters . Dallas, the most insecure, mean-spirited city in the country, sizeable parts of which would throw big parties every November 22nd if they could get away with it**, hasn’t officially denounced this book, and I’d have thought that the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, or the many fulminating reactionary textbook activists there who contribute so much to keeping Texans stupid, would have held press conferences, marches, and bookburnings over this book and its contents.

. Dallas, the most insecure, mean-spirited city in the country, sizeable parts of which would throw big parties every November 22nd if they could get away with it**, hasn’t officially denounced this book, and I’d have thought that the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, or the many fulminating reactionary textbook activists there who contribute so much to keeping Texans stupid, would have held press conferences, marches, and bookburnings over this book and its contents. Nope. Nothing from the East Coast, or the Left Coast, both of which have well-founded grudges against Texas, only in part on account of our most recent ex-president, grudges that could be

Nope. Nothing from the East Coast, or the Left Coast, both of which have well-founded grudges against Texas, only in part on account of our most recent ex-president, grudges that could be  readily slaked by the handy and complete demolition of the Texas founding myth done here. Unfortunately for them, they are likely to get a new dose of grudges from the impending Perry presidency, alas. Them and the rest of us, alas squared.

readily slaked by the handy and complete demolition of the Texas founding myth done here. Unfortunately for them, they are likely to get a new dose of grudges from the impending Perry presidency, alas. Them and the rest of us, alas squared.

The Anatomy of the Last Stand Myth, by Phillip Thomas Tucker. Published in 2010 by second-tier publishers Casemate, this book has not received any reviews by any major national source, nor any attention by any of the Texas newspapers.* Hell I’d have thought that San Antonio,

The Anatomy of the Last Stand Myth, by Phillip Thomas Tucker. Published in 2010 by second-tier publishers Casemate, this book has not received any reviews by any major national source, nor any attention by any of the Texas newspapers.* Hell I’d have thought that San Antonio, Nope. Nothing from the East Coast, or the Left Coast, both of which have well-founded grudges against Texas, only in part on account of our most recent ex-president, grudges that could be

Nope. Nothing from the East Coast, or the Left Coast, both of which have well-founded grudges against Texas, only in part on account of our most recent ex-president, grudges that could be  readily slaked by the handy and complete demolition of the Texas founding myth done here. Unfortunately for them, they are likely to get a new dose of grudges from the impending Perry presidency, alas. Them and the rest of us, alas squared.

readily slaked by the handy and complete demolition of the Texas founding myth done here. Unfortunately for them, they are likely to get a new dose of grudges from the impending Perry presidency, alas. Them and the rest of us, alas squared.Tucker, a historian for the USAF, brings to the table the essential military knowledge necessary to write about a military event. All previous authors about the Alamo were journalists who knew nothing about military matters and the battlefield, or second-tier academics, who all were equally ignorant. Both groups most all lack facility in the Spanish language, and neither group ever did any real research into Mexican archives for the firsthand accounts of participants that Tucker found when he went looking in Mexican archives. Both groups either lazily and uncritically promoted the Alamo myth, or, perhaps worse, saw where the evidence led and shied away from drawing the necessary if unpopular conclusions. Doesn’t say much for either

equally ignorant. Both groups most all lack facility in the Spanish language, and neither group ever did any real research into Mexican archives for the firsthand accounts of participants that Tucker found when he went looking in Mexican archives. Both groups either lazily and uncritically promoted the Alamo myth, or, perhaps worse, saw where the evidence led and shied away from drawing the necessary if unpopular conclusions. Doesn’t say much for either group.

group.

equally ignorant. Both groups most all lack facility in the Spanish language, and neither group ever did any real research into Mexican archives for the firsthand accounts of participants that Tucker found when he went looking in Mexican archives. Both groups either lazily and uncritically promoted the Alamo myth, or, perhaps worse, saw where the evidence led and shied away from drawing the necessary if unpopular conclusions. Doesn’t say much for either

equally ignorant. Both groups most all lack facility in the Spanish language, and neither group ever did any real research into Mexican archives for the firsthand accounts of participants that Tucker found when he went looking in Mexican archives. Both groups either lazily and uncritically promoted the Alamo myth, or, perhaps worse, saw where the evidence led and shied away from drawing the necessary if unpopular conclusions. Doesn’t say much for either group.

group.Tucker shows, from contemporaneous Mexican and American accounts, that there was no fight to the last man at the Alamo. Instead, the defenders, who were caught completely flat-footed asleep by a surprisingly well-planned and executed Mexican attack, mostly all bolted and ran from the Alamo and were cut down by Mexican cavalry that Santa Anna had placed in position for that task. A sizeable contingent of defenders were in the ‘hospital’ and were massacred there, and there was a cluster of defenders, led by Dickenson, who fought bravely in the Alamo chapel in an effort to buy time for their comrades’ escape. Even with their bravery, the fight was over inside of twenty minutes, start to finish. No real battle winds up that quick; it was an ignominious rout.

A sizeable fraction, half or better probably, of Mexican casualties (which totalled around 300) were friendly-fire casualties, from the untrained Mexican infantry firing blindly, from the hip, in the dark, into the backs of their countrymen. Contrary to the Old Joe myth, there were in  fact two escapees from the slaughter, and they were interviewed, and their accounts got circulation at the time. The flight from the Alamo appears to have been the defenders’ plan all along, and Tucker argues that if Santa Anna had postponed his attack for a day or so that the defenders would have sought surrender terms on account of the severe morale, illness, and command dissention problems in the Alamo garrison. The lack of interest in preserving the Alamo, which was mostly demolished before the DRT saved what was left of it 60 years later, shows not just the ordinary extraordinary greed and shortsightness of Texans, but also likely shows that the Alamo myth wasn’t entirely accepted by a fair or better percentage of the people who lived then. The failure of anyone in San Antonio to gather the defenders’ ashes from the burn piles afterwards–they were almost all left untouched for the two or so years it took for the winds to disperse them–also shows that there was no real love lost between San Antonio’s

fact two escapees from the slaughter, and they were interviewed, and their accounts got circulation at the time. The flight from the Alamo appears to have been the defenders’ plan all along, and Tucker argues that if Santa Anna had postponed his attack for a day or so that the defenders would have sought surrender terms on account of the severe morale, illness, and command dissention problems in the Alamo garrison. The lack of interest in preserving the Alamo, which was mostly demolished before the DRT saved what was left of it 60 years later, shows not just the ordinary extraordinary greed and shortsightness of Texans, but also likely shows that the Alamo myth wasn’t entirely accepted by a fair or better percentage of the people who lived then. The failure of anyone in San Antonio to gather the defenders’ ashes from the burn piles afterwards–they were almost all left untouched for the two or so years it took for the winds to disperse them–also shows that there was no real love lost between San Antonio’s  inhabitants and the persons claiming to be their defenders. That, and a desire of most Texans back then to forget the Alamo, as time enough hadn’t transpired for the myth to displace most people’s back then ordinary doubts about what actually happened. I suspect that the

inhabitants and the persons claiming to be their defenders. That, and a desire of most Texans back then to forget the Alamo, as time enough hadn’t transpired for the myth to displace most people’s back then ordinary doubts about what actually happened. I suspect that the contemporaneous newspaper storytelling about the Alamo, which all began the fight to the last man myth, wasn’t entirely believed by the readership. People could smell a rat back then, probably better than now.

contemporaneous newspaper storytelling about the Alamo, which all began the fight to the last man myth, wasn’t entirely believed by the readership. People could smell a rat back then, probably better than now.

fact two escapees from the slaughter, and they were interviewed, and their accounts got circulation at the time. The flight from the Alamo appears to have been the defenders’ plan all along, and Tucker argues that if Santa Anna had postponed his attack for a day or so that the defenders would have sought surrender terms on account of the severe morale, illness, and command dissention problems in the Alamo garrison. The lack of interest in preserving the Alamo, which was mostly demolished before the DRT saved what was left of it 60 years later, shows not just the ordinary extraordinary greed and shortsightness of Texans, but also likely shows that the Alamo myth wasn’t entirely accepted by a fair or better percentage of the people who lived then. The failure of anyone in San Antonio to gather the defenders’ ashes from the burn piles afterwards–they were almost all left untouched for the two or so years it took for the winds to disperse them–also shows that there was no real love lost between San Antonio’s

fact two escapees from the slaughter, and they were interviewed, and their accounts got circulation at the time. The flight from the Alamo appears to have been the defenders’ plan all along, and Tucker argues that if Santa Anna had postponed his attack for a day or so that the defenders would have sought surrender terms on account of the severe morale, illness, and command dissention problems in the Alamo garrison. The lack of interest in preserving the Alamo, which was mostly demolished before the DRT saved what was left of it 60 years later, shows not just the ordinary extraordinary greed and shortsightness of Texans, but also likely shows that the Alamo myth wasn’t entirely accepted by a fair or better percentage of the people who lived then. The failure of anyone in San Antonio to gather the defenders’ ashes from the burn piles afterwards–they were almost all left untouched for the two or so years it took for the winds to disperse them–also shows that there was no real love lost between San Antonio’s  inhabitants and the persons claiming to be their defenders. That, and a desire of most Texans back then to forget the Alamo, as time enough hadn’t transpired for the myth to displace most people’s back then ordinary doubts about what actually happened. I suspect that the

inhabitants and the persons claiming to be their defenders. That, and a desire of most Texans back then to forget the Alamo, as time enough hadn’t transpired for the myth to displace most people’s back then ordinary doubts about what actually happened. I suspect that the contemporaneous newspaper storytelling about the Alamo, which all began the fight to the last man myth, wasn’t entirely believed by the readership. People could smell a rat back then, probably better than now.

contemporaneous newspaper storytelling about the Alamo, which all began the fight to the last man myth, wasn’t entirely believed by the readership. People could smell a rat back then, probably better than now.

The defenders did an embarrassingly bad job of reinforcing the fortifications while they had the chance; mostly out of their unwillingness to do manual labor with pick and shovel. Holding the Alamo was a first-class strategic mistake, as it neither barred Santa Anna from San Antonio’s resources nor prevented him, should he have decided to, from bypassing it and attacking instead the Texian center of resistance in East Texas, and thereby quickly and handily defeating the revolt. The Texians own decision to stay in the Alamo was in large part based on the large numbers of cannon they had there, and their unwillingness to abandon them to the Mexicans. The cannon did them no good during the battle, as they lacked the manpower to crew them, the emplacements to use them, and neither the projectiles or powder to fire them. A terrible mistake, holding the Alamo for its cannon, one that was stupefyingly obviously militarily wrong. Houston’s unwillingness to send relief to the Alamo may have been from his chronic drunkenness (and likely opium stupefaction) but a part of it was likely his and other politicians in Washington-on-the-Brazos’ desire to remove from the scene several political rivals, Crockett foremost. That, and there was a considerable class rivalry between the white po-boy drifters holed up in the Alamo and their East Texas planter betters–the Texas Revolution was yet another rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.

The majority of the book, like most accounts of the Alamo, is a recounting of the events that led to the Texas secession from Mexico in 1835-6. The elephant in Texas history’s living room has always been, of course, slavery, and even my 7th grade Texas History textbook 35 years ago mentioned that the Texas founding fathers were slaveholders. Most historians haven’t done that much better a job of facing that elephant since, but Tucker does the best job to date of pointing out how that issue was the key issue that drove Texas secession. Slaves and cotton equalled wealth and status here in the US back then, and obtaining that combination was unquestionably the best and most accessible ladder up that an ambitious white male back then had. Texas’ white settlers came here from the first, even before Moses Austin’s efforts, with that goal in mind. The conflict between Anglo and Mexican in Texas was most of all a conflict between Anglo slaveholders and wanna-be slaveholders and a Mexico newly freed from European peonage’s deep desire to eliminate slavery in its borders. American historians have over the years danced around, or at best dealt gingerly at a distance, with this fact. Tucker lays it out, plainly and directly, better than I’ve seen elsewhere.

What the textbooks then, and most histories still now, don’t mention is what a lot of scoundrels, greedheads, and sorry hustling-assed lowlifes the Texas Republic leaders were. They were all, every last one of them, dreadfully militarily incompetent and only a few of them were even marginally capable of the political leadership that a successful revolt requires. Fortunately for Anglo Texas, Santa Anna made two fatal mistakes–investing the Alamo and napping at San Jacinto that afternoon. Grant, in his memoirs, talking about his experiences in the Mexican War, said that we the US were lucky to be fighting an enemy like the Mexicans, or else, he said, we’d have been taught some hard lessons. Same was true in 1836, Mexican military incompetence matched by Santa Anna’s political incompetence. Tucker doesn’t preach about this; he just lays out the facts, which speak for themselves.

Tucker has a decent discussion of how the Alamo myth functioned in the 19th Century to provide a rationalization of Anglo racial superiority, the theft of Texas from Mexico, and the subsequent dispossession, exclusion and marginalization of Tejanos from position and property. Where the book fails is bringing the Alamo myth into the 20th century, and for that matter, the 21st. The Disney and John Wayne ’50′s glorification makes some sense in the light of American Cold War insecurities, but why Disney revisited it five years ago needs explanation. Was it a commercial pastiche, or a re-hashing of a myth to serve domestic war politics a second time, for a (series of) war(s) even more fraudulent and unnecessary than the Cold War?

The book has its flaws. It is in dire need of proper editing, and could usefully have been shrunk by a third or better in length. Tucker is no shakes as a prose stylist. There are suppositions about events and motivations in the Alamo that are good suppositions, but lack documentation enough to be presented as facts. But there is hidden within a delightful secret to this book that won’t be obvious to most ahistorical Americans, but one obvious to Clio’s servants and admirers. This book will give social scientists a test case the likes of which has never before happened. A widespread and deeply held founding myth has been destroyed by this book, and this provides a unique opportunity to study the diffusion and struggle of truth versus myth. How many years will it take to change the textbook accounts? How long before Americans acknowledge that the Alamo was a chapter of military ignominy and embarrassment, and not an epic of heroism? Will latinos pick up on this book, and use it for their political and social struggles? How will this story fare in other countries’ histories of us? I am looking forward to how things develop on these fronts–it is a truly rare opportunity to learn about ourselves, how we think, how we come to hold our beliefs. I am pleased to do my bit by publicizing this book, to advance truth against myth, to kill the lies that have been deliberately spread, and to expose the professional incompetence and pusillanimity of the official and influential. My congratulations to the author, for a fine and overdue and much needed book.

*Both the Guardian and the Daily Mail in the UK reviewed it, interestingly enough. They both liked it.

**Shoot I’m being too mean to Dallas here. Contrary to what too many braindead Yankees still like to think, Dallas was then and has always remained embarrassed by its (very limited) responsibility for the death of JFK. On the other hand, this statement is absolutely true about Miami, at least amongst the guisano cubanos.

foundry and dixon

foundry and dixon

(1).jpg)